Welcome to the second installment of my deep dive into extrapolating lessons on craft from other written work! (Missed out on Part I? Find it here!) This is something I do all the time to learn new techniques and level up my understanding of craft, and I thought it might be nice to share. In this instance, we’re focusing specifically on The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson and its influences on my short story, “Vanishing Point,” which you can find in the new YA horror anthology The House Where Death Lives, edited by Alex Brown.

Last time I talked about the importance of paying attention (WHAT effect does this have on me?) and of wonder (WHY might this effect be intentional?). Today I’d like to walk you through the rest of my process, which involves studying an author’s craft and forming takeaways I can use in my own work. So we’re all on the same page, we’re looking specifically at Chapter 5, Scene 4 of Hill House, which you can find in my last newsletter here.

This passage has so much to dive into, so many techniques at play, but in the interest of efficiency, I’ll focus just on Jackson’s voice—that is, the way the narrator tells the story, including attention, image, and language—and more specifically on the elements that inspired the voice in “Vanishing Point.”

After identifying an effect—in this case, the creeping, lurking feeling that something is seriously, sinisterly wrong—my next step is to ask, WHERE is this effect most prominent? If there’s an effect, there must be a cause, so I look for examples where I felt it most strongly. Then, with something to study, the next question is always (and now we’ve reached the heart of the matter), HOW does this effect come through on the page?

In other words, What CRAFT is at work here, creating this effect? Let’s look at three examples where I really felt that creeping, lurking feeling, or where the story made me really go 😬.

Example 1: ECHOES

From the room next door, the room which until that morning had been Theodora's, came the steady low sound of a voice babbling, too low for words to be understood, too steady for disbelief. Holding hands so hard that each of them could feel the other's bones, Eleanor and Theodora listened, and the low, steady sound went on and on, the voice lifting sometimes for an emphasis on a mumbled word, falling sometimes to a breath, going on and on.

Notice how much repetition there is in Jackson’s voice: two repetitions of “room,” two variations of “the steady low sound,” two more in “too low” and “too steady,” with three repetitions each of “steady” and “low,” and two of “sometimes” and “on and on.” In another piece of writing, I suspect these repetitions would be edited out, but in Hill House, I hear them as creating echoes. A dripping faucet down the hall. A whisper in a distant room. I think it works atmospherically—this is a story about a haunted house, after all—but it’s also like things can’t just exist as they are. They have to continually reassert themselves: I’m here. I’m here. Steady and low, steady and low. I’m here. It makes me think of things trying to claw their way back into reality, trying to remain here, even if they no longer belong.

It’s creepy in Chapter 5, in a scene with a disembodied voice in a haunted house, but these echoes and repetitions appear even before Eleanor reaches Hill House, and the effect is the same. Take this snippet of dialogue between Eleanor, her sister Carrie, and Carrie’s husband, as she tries to convince them to let her borrow the car so she can get to Hill House:

“I just don’t think she should take the car, is all,” Eleanor’s brother-in-law said stubbornly.

“It’s half my car,” Eleanor said. “I helped pay for it.”

“I just don’t think she should take it, is all,” her brother-in-law said. He appealed to his wife. “It isn’t fair she should have the use of it the whole summer, and us have to do without.”

“Carrie drives it all the time, and I never even take it out of the garage,” Eleanor said. “Besides, you’ll be in the mountains all summer, and you can’t use it there. Carrie, you know you won’t use the car in the mountains.”

“But suppose poor little Linnie got sick or something? And we needed a car to get her to the doctor?”

“It’s half my car,” Eleanor said. “I mean to take it.”

“Suppose even Carrie got sick? Suppose we couldn’t get a doctor and needed to go to a hospital?”

“I want it. I mean to take it.”

Here, the characters are echoing themselves as well as each other. There are repetitions within the same paragraph: “you’ll be in the mountains all summer, and you can’t use it there”/“you won’t use the car in the mountains.” There are repetitions in a single character’s dialogue spread out across the entire passage: “It’s half my car.”/“I mean to take it.” And there are even repetitions between the different characters, most notably with the word “car,” which appears in this short excerpt five times. It’s like the characters are all talking, but no one’s listening to each other. More than that, to me it feels like they’re in different rooms of a vast and cavernous mansion—an effect underscored by the lack of description or action in the scene—so that all that they can hear are the echoes of the others—all the rest is swallowed up by the distance between them.

Example 2: FLATTENING

We left the light on, she told herself, so why is it so dark? Theodora, she tried to whisper, and her mouth could not move; Theodora, she tried to ask, why is it dark? and the voice went on, babbling, low and steady, a little liquid gloating sound.

Setting aside the perfect, disgusting mouthfeel of that last description, I want to point out how Jackson doesn’t often distinguish between Eleanor’s thoughts and the action of the scene. A thought is the same as a description is the same as an action is the same as the imagination. In another story, this sentence might be broken up with italics: “We left the light on, she told herself, so why is it so dark? Theodora, she tried to whisper, and her mouth could not move; Theodora, she tried to ask, why is it dark?” Instead, all the text reads as if it’s on the same level, differentiated only by punctuation, usually commas, which blurs the internal with the external, the paranormal with the real. What this means for me is that in Eleanor’s perspective, reality is not concrete. It cannot be relied upon. It doesn’t operate by the laws of physics or logic but by some unknowable, horrific chaos lurking beneath the veneer of reality.

Example 3: INTERRUPTIONS

She rolled and clutched Theodora's hand with both of hers, and tried to speak and could not, and held on, blindly, and frozen, trying to stand her mind on its feet, trying to reason again.

Have you noticed how many commas Jackson uses, how many ways the narrator interrupts herself or adds on a half-formed thought? Let’s look at them all, separated out into lines for easier viewing:

She rolled and clutched Theodora’s hand with both of hers,

and tried to speak and could not,

and held on,

blindly,

and frozen,

trying to stand her mind on its feet,

trying to reason again.

First comes the base clause, “She rolled and clutched Theodora’s hand with both of hers,” followed by “and tried to speak and could not,” which refers back to “She.” To me, the second clause feels truncated on both ends, like pieces have been lopped off: “[she] tried to speak and could not [speak].” This is followed by an even shorter clause—“and held on”—again referring back to “She,” again feeling truncated with the preposition dangling there at the end. (What is she holding on to?) It feels to me as if the narration is broken but trying to piece itself together somehow. Similar to the flattening effect between Eleanor’s internal world and the external one, it’s like reality isn’t cut-and-dry anymore; it isn’t straightforward; it goes in fits and starts and is never quite sure where it is or where it’s going. (Brilliantly, in this scene in particular, it also mimics the sound of the voice babbling incoherently on the other side of the wall.)

Then come my favorite interruptions, and they’re truly interruptions this time. I love the interjections of “blindly, and frozen,” because they’re just a tiny bit off-kilter. I think we might expect here, for balance, two -ly adverbs, but that’s not what we get. “Blindly” is an adverb modifying the way Eleanor “held on,” but “frozen” is modifying Eleanor herself, all the way back to “She” again. “[B]lindly” and “frozen” aren’t a pair, although reasonably they should be. Instead, they’re completely out of step with one another, describing two different things in two different parts of the sentence, their dissimilarity made even more apparent by use of the comma and the conjunction. They’re breaks in the balance of the world, an indication that something is not level, not rational, not normal, not okay.

Lastly, there are those two participial phrases, “trying to stand her mind on its feet” and “trying to reason again.” In rhetoric, this technique is called anaphora—the repeated word at the beginning of successive clauses (or in this case phrases)—and I think the repetition here speaks to Eleanor’s desperation. The interruptions in this sentence show the world is broken, it doesn’t make sense, it is unknowable and terrifying, and the repeated phrases at the end attempt to heal that brokenness, at least in their content, as Eleanor tries “to stand her mind on its feet” and “to reason.” But the repetition shows that she is failing; in fact, it could be said that her narration is contributing to the brokenness, like a skipping record.

So there are three ways that Jackson crafts the voice in Hill House, creating this creeping, lurking feeling that something is seriously, sinisterly wrong: 1) She uses repetition to create echoes in spaces where echoes wouldn’t logically occur. 2) She eliminates formatting distinctions between the internal world and the external, thus removing the distinctions between the imaginary/paranormal and the real. 3) She writes sentences that interrupt one another in ways that speak to the breaking of reality.

With that in mind, I’d love to show you how I applied similar techniques to “Vanishing Point,” because the final step for me is, NOW, how can I do this myself, in my own work?

Example 4: “VANISHING POINT”

Here’s the first page of my story, “Vanishing Point,” which is about a fifteen-year-old girl named Viv grappling with the loss of her mother, who died in a room at the far end of a hallway that Viv has always suspected to be longer and more sinister than it appears:

There was something wrong with the second-floor hallway. Viv did not even like to set foot in it, if she could avoid it, which she did at all costs.

“It’s just a room,” Mom had said once, sashaying through her door near the end of the hall, her singsong voice floating, disembodied, back to Viv. “A room in a house.”

But it had never been just a room, had it? Frowning, Viv watched Bachan wipe down the console table that spanned one side of the hall. Real rooms had purposes: the bathroom for bathing, the dining room for dining, the living room for living…

And the hallway was not a room for living. It was not a place meant for staying, inhabiting, dwelling. The hallway’s only purpose was transitory; it spirited you from one real room to another.

Years ago, while reading House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski, which is, among other things, about an infinite house, I remember being so struck by the word association “hallways”/“always,” both evoking the imagery of a never-ending hallway as well as evoking the echoes such a space might create. So when Alex offered me the chance to write about a room in a haunted house, I knew I wanted to write about a hallway. “Vanishing Point” takes place entirely in this one room of the house, so in order to give it that feeling of being a much vaster space, I set out to create echoes on the very first page.

Notice the repetitions, first in Mom’s dialogue: “It’s just a room.”/“A room in a house.” Mom is a character who is already dead by the time the story begins, so it’s fitting that her dialogue is a little heightened, more like a memory, more like a ghost. Her words are described as “singsong,” which hopefully lend to the echoes that follow a similar musicality, not rhymes but repetitions, simplistic as a child’s lullaby: “bathroom for bathing,” “dining room for dining,” “living room for living.” Then of course, there’s “room” itself. It appears six times on the first page, announcing to the reader, again and again, its overbearing and unavoidable presence.

And then there are the interruptions, which occur in the first paragraph but really take off in the second:

“It’s just a room,” Mom had said once,

sashaying through her door near the end of the hall,

her singsong voice floating,

disembodied,

back to Viv.

“A room in a house.”

It’s Mom, again, who takes the language of the story to a more heightened dimension. The interruptions in this sentence underscore the separation between Mom’s body, “sashaying through her door near the end of the hall,” and her words, which remain trapped in the hallway. Hopefully, the constant interruptions show that this memory of Mom is in fragments, distorted like a broken mirror, with that emphasis on “disembodied” splitting the passage even further by slicing it at the halfway point.

In addition, I tried to flatten the narration in “Vanishing Point” by using free indirect discourse, in which the character’s thoughts (“But it had never been just a room, had it?”) bleed into the action and description (“Frowning, Viv watched Bachan wipe down the console table that spanned one side of the hall”). Later, I draw on Jackson’s techniques for collapsing the internal world and the external when I keep Viv’s interior monologue in roman type, rather than italics, like in this passage where Viv thinks she sees her mother in the hallway:

Her mother did not reply, did not even turn, but continued through her bedroom door, swaying on ankles that were much too small, impossibly small for her, the ankles of a child or a bird. They shouldn’t have been able to hold her up, Viv thought later. How could they be holding her up?

This paragraph is also riddled with interruptions, now laced with desperation. The first clauses, “Her mother did not reply, did not even turn” employ repetition to show how Viv’s brain is trying to make sense of what she’s seeing, as do the later interruptions: “too small, impossibly small for her, the ankles of a child or a bird.”

In “Vanishing Point,” Viv’s grief over her mother’s death is so great that it’s all-consuming, distorting her perception of reality. Like Eleanor, she can no longer tell what is real and what is imaginary (or perhaps paranormal), so like Eleanor, her thoughts are undifferentiated from the rest of her narration: “They shouldn’t have been able to hold her up, Viv thought later. How could they be holding her up?” To Viv, the internal is the same as the external is the same as the paranormal is the same as the real. The person she sees in the hallway could be her mother, but it’s equally possible that it’s a figment of Viv’s imagination, a ghost, something else entirely, or some horrifying combination of all of these.

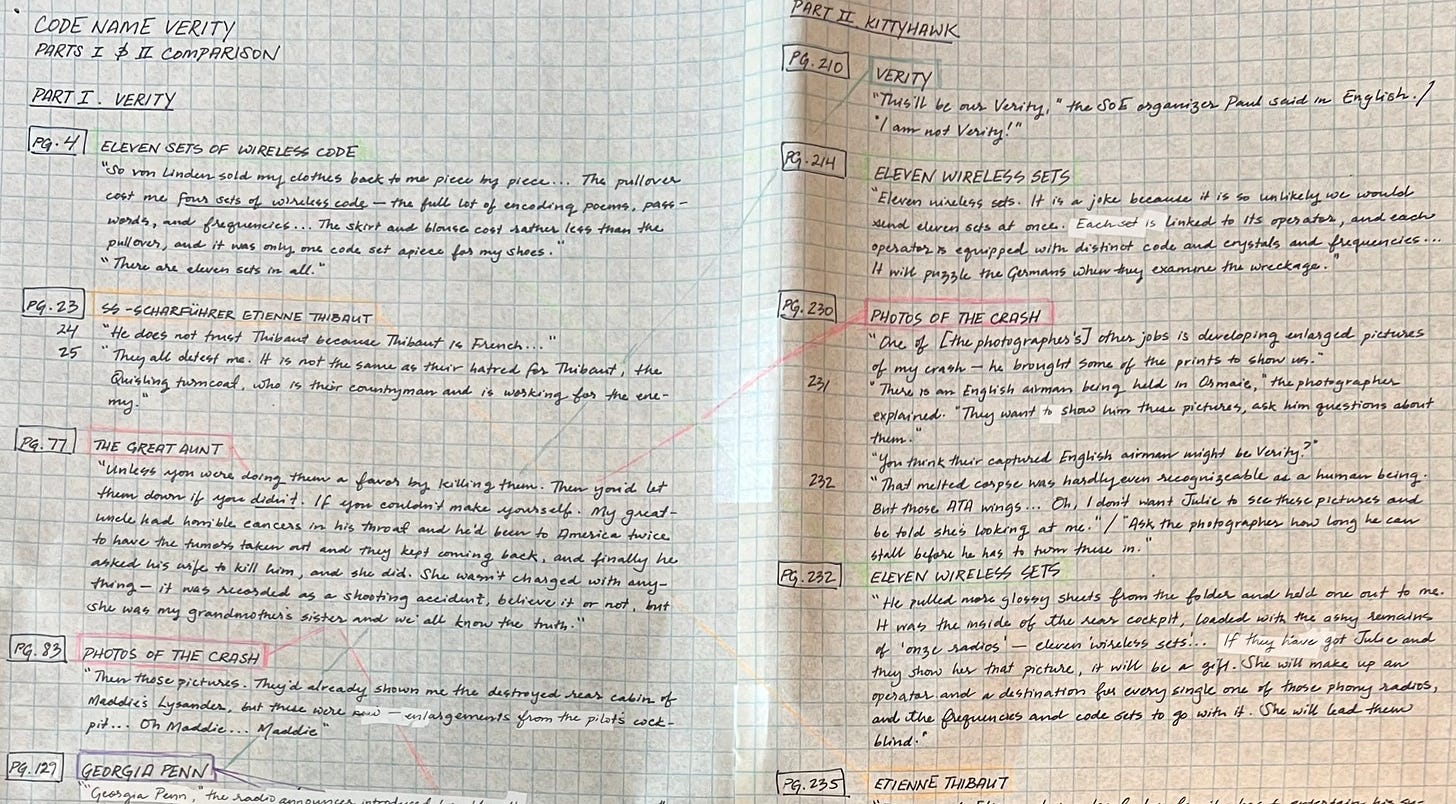

I’m not always this thorough when it comes to extrapolating lessons on craft from other written work, but if you flip through my notebooks, you’ll find that they’re filled with reverse outlines (like this one of Seven Samurai), maps like the one of the different connections between the two halves of Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein (major spoilers, so don’t look too closely!), and notes on literary techniques.

For me, knowing how to learn, explicitly, from other people’s writing means that the possibilities for growth are as limitless as the number of books you can read, and the lessons you learn can be applied to practically anything. A technique from adult horror can be used in YA, for example, or a middle grade mystery or a romance. And learning new skills like this means you don’t always need a class (although they’re great) or even a book on craft. All you need are your powers of observation, your curiosity, and your ability to extrapolate based on the knowledge you already have.

If you’re looking for more examples of how writers learn from other work, my friend

(Strange Exit) is great at this—it’s always fascinating, seeing what she pulls out of a story!—and she details her thoughts and observations regularly in her Substack, The Writer’s Attic.I also highly recommend checking out

(Afterword), one of my professors from San Francisco State. Nina taught me so much about close-reading sentences, just like I’ve done here, and you can learn more about her process in her book, How to Write Stunning Sentences, as well as in her Substack, Stunning Sentences.Now, one last time, for the folks in the back, here’s my process and the questions I ask:

WHAT effect does this have on me?

WHY might this effect be intentional?

WHERE is this effect most prominent?

HOW does that effect come through on the page? (What CRAFT is at work here, creating this effect?)

NOW, how can I do this myself, in my own work?

Upcoming

On Saturday, September 28, join me, Tara Sim, Robin Ha, Markelle Grabo, and R.M. Romero for a virtual panel on YA fantasy retellings, hosted by Lili at Utopia State of Mind! Panel starts at 1pm ET/10am PT, and it would be so lovely to have you there! Tune in here and tell your friends!