Today’s post is a decade in the making.

I wrote the first part of it in 2015, a few months after I signed with my literary agent and then the book deal for The Reader, which was to come out in 2016. It’s about querying, rejection, and a book art project called DOUBTS, which I created while in the depths of creative paralysis and despair.

The second part is a more recent reflection, ten years later, on querying and the creation of DOUBTS. I didn’t know at the time how much that fun little project would teach me, but what I learned from DOUBTS continues to inform the way I cope with feelings of rejection, inadequacy, and failure, and I’d like to share some of those thoughts with you.

DOUBTS

Traci Chee

2015

c1950s glass medicine bottle, vegetable cellulose capsules, non-pareils, tissue paper, ink

I submitted my first short story for publication in 2006.

Unsurprisingly, it was rejected.

Thus began my adventures in publishing. I joined the thousands of other writers who have to swallow rejection on a daily basis, who accept their rejections as rites of passage, as payment of their dues, as the lashes they must take while they march onward through the perils and pitfalls of their artistic journeys.

In the nine years since then, I’ve racked up 49 additional rejections, ranging from the impersonal “Dear Author”s to the painful “not strong enough”s. Most were kind. Some were not. And in 2014, as I slogged through the query trenches in search of a literary agent, this life of rejection finally dragged me under.

I thought I knew what I was getting into. I’d done my research, after all. I’d read the statistics. I knew the likelihood of squeaking by with only a handful of rejections before an agent recognized my genius was a distant dream, a rumor whispered behind bookshelves and steaming coffee cups, but never a reality.

I wasn’t prepared. Not in the slightest.

After I sent my first batch of queries, I became obsessed with checking my email. Refresh. Refresh. Refresh. Every twenty minutes. Every ten minutes. Every two minutes. Maybe something came in. Maybe someone requested my manuscript. Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

The rejections trickled in. Never fast enough to satisfy me. Never with enough information to help. I was riddled with uncertainty. Should I revise my query? My first ten pages? My whole manuscript? Should I trunk the idea entirely? Was I failure of the most gigantic proportions, completely oblivious to how awful my writing really was?

I tried to distract myself by writing another book, but there was no joy in it anymore. Whenever I faced the page, all I felt was fear and anxiety and self-doubt. It was like rejection had robbed me of my ability to work.

And I loved the work.

I needed to get my mojo back.

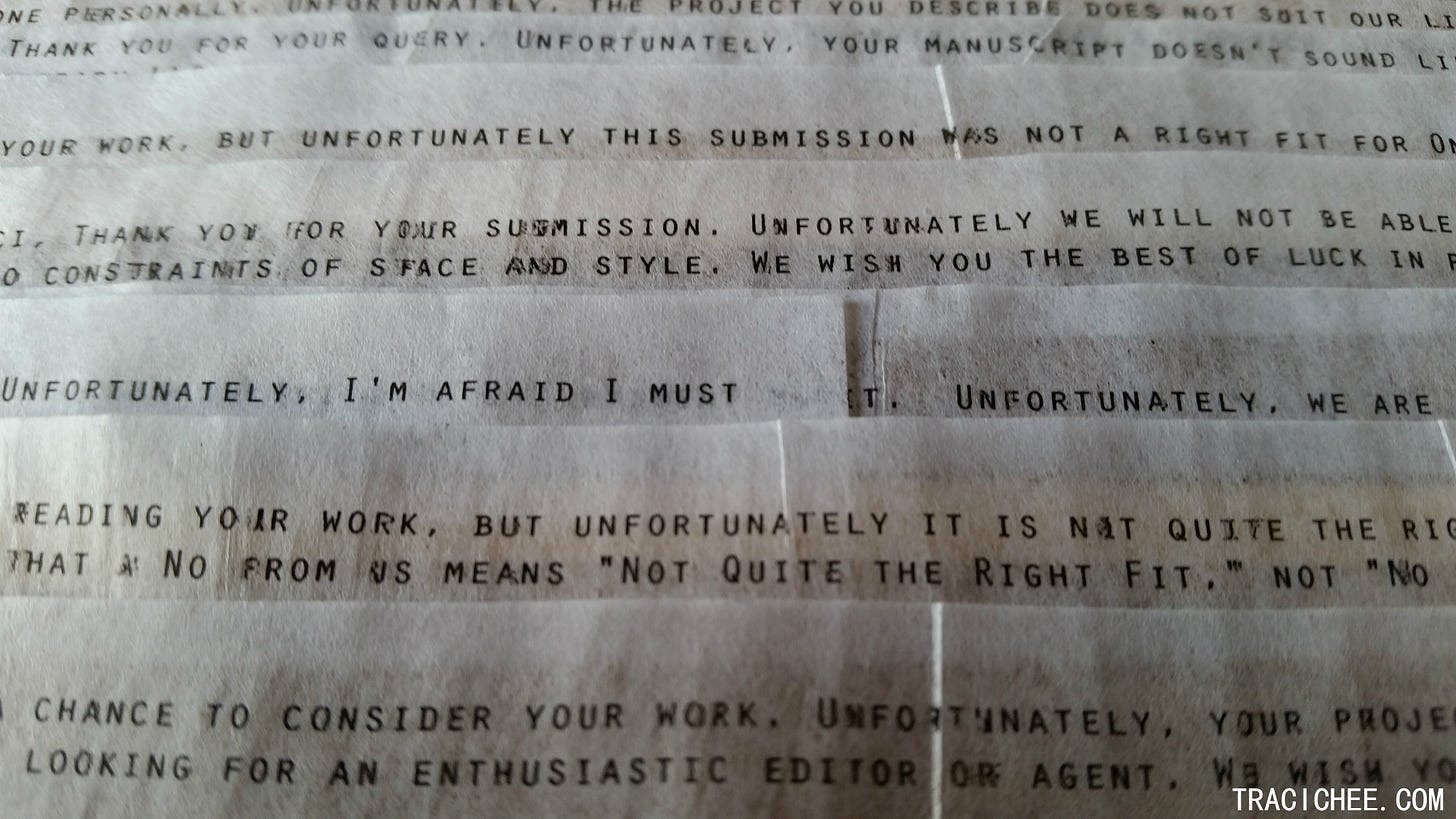

DOUBTS arose from this need to turn my dejection and despair into something creative and positive. I needed to build something. Something that would help me laugh off all the “unfortunately”s and “just didn’t love it enough”s. Something that would help me take the power out of rejection and claim it for myself. Something weird and booky and full of joy.

DOUBTS is a compendium of 50 rejections collected from 2006-2014, and as far as books go, it’s a little on the unconventional side. The binding is a vintage pill bottle with a rusty metal cap. The cover is a label, complete with dosage directions. Each page is an edible capsule containing one rejection—verbatim, with the date of receipt. The story is one of epistolary and memoir, pain and transformation. And also one of hope.

Yes, rejections are bitter medicine. They’re also battle scars and badges of honor. They’re proof that I’m trying. That I’m chasing this wild dream of doing what I love. And when my books are published, I’ll be able to shake all my rejections in their little bottle, cackling madly, because I didn’t let them stop me.

I’m not done with rejection. In this business, there are always going to be more of them lying just around the next submission, waiting to pounce. But when that happens, when the “just not for me”s and “not a good fit”s start rolling in again, offering nothing but despair and discouragement, at least I’ll have this.

Because if it ever comes down to it, if I’m ever impulsive and desperate enough, I’ll literally be able to swallow my doubts.

Onward, writers. There are books to be made.

I hate rereading my old work. (I actually haven’t read The Reader Trilogy since it was published!) Too frustrating. Too cringe. It’s me, but it’s not me. It’s my voice, but it feels like a fizzy old recording—smaller, younger, more impatient, less reserved.

But not wrong. I still remember the obsession, the uncertainty, the fear and doubt and resentment.

It was like rejection had robbed me of my ability to work.

And I loved the work.

That sensation still lives in me. In my nerves.

Recently, a friend and colleague from my undergrad program at UC Santa Cruz, A.M. Hogan, wrote about her search for an agent—the process of sending out queries, the dark night of the soul, the offer to revise and resubmit—and at the end of her post she invited others to share what they’d learned from their own querying journeys.

I thought of the dread, the hope, the creative paralysis, and the defiance, too, that I put into DOUBTS.

What had I learned from all that?

I’ve talked before about how much I love writing. I love the puzzle of it, the ambition of it, the grind. That love, for me, is enduring, but, as I learned from querying, it can also be fragile.

If all it takes is a little self-doubt to stymie my creative spirit, to turn it cold and inert, that means my creative spirit must be protected. Vigilantly.

This is the lesson I learned from querying, and it’s a lesson I’ve had to re-learn over and over, because I’m continually discovering new reasons to doubt myself: not enough buzz, not enough followers, not enough likes, not enough engagement, not enough support, not enough sales, not enough in the budget, not enough press, not enough readers, not enough stars... The list goes on and on.

I think these doubts are unavoidable, to some extent. Comparison and competition are part of selling anything, including books, and they lead almost inevitably to me feeling, in one way or another, like I’m not enough.

So, then. What to do?

How do I protect my creative spirit? My love of storytelling? My joy? My creativity is the root of my entire career—without it, there are no queries, no submissions, no deals, no budget, no press, no sales, no victories, defeats, doubts, books, writing, or work. (And I love the work.) So it must be shielded, strengthened, and allowed to flourish.

I think the ways we protect our creativity are very individual—what works for one person may not work for another, what works at one time may not work at another—but I’d like to share some of my own approaches and how they have worked for me over the years.

A decade ago, when I was paralyzed by doubt, I found another outlet for my creativity. (Can’t write a book? Make book art!) But in the years since, I’ve found other forms of protection too.

I try run my own race. I’ve heard people say, “Keep your eyes on your own paper,” by which they mean, “Focus on your own work and progress, not anyone else’s,” but I think the analogy evokes test-taking, and we’re not all taking the same test. I’m not trying to write the same books everyone else is writing. I’m trying to write my own books in my own way with my own background, skills, and limitations. In other words, I’m trying to run my own race, and in that race the terrain is different, the weather is different, the milestones are different, even the finish line is different. Some doubts are unavoidable—rejections are rejections, after all—but if I remember to run my own race, then at least I’m not comparing my shortcomings to anyone else’s, or, worse, my shortcomings to someone else’s success.

I am part of a support system. I have friends who are writers, many of them from my debut year. Some of them have witnessed every step of my publishing journey—as I have witnessed theirs—and together we celebrate, commiserate, encourage, bristle, bemoan, listen, share, and generally remind each other that in this business, we are not alone. Equally as valuable, I also have friends and family who aren’t writers, and their perspectives remind me that there is more to me than my writing, and there is more to the world than my job.

I focus on the writing. As I wrote in my post about dreams, I try to remember that so much of publishing is out of my control (and therefore not worth carrying around with me). The only thing about this industry that I truly control is the writing, which means that success and failure do not have to be linked to anyone or anything else—not rejections, not deals, not sales, not accolades—but to what is important to me.

Did I write the story I needed to write in the best way I knew how? Did I push myself to grow as an artist? Did I tell a story that I believe was worth telling? Did I do it in a way consistent with my values?

I try to separate my love of the work from my desire for external validation. What I love about writing is mostly internal and intrinsic to the writing itself. I love brainstorming. I love making timelines and maps. I don’t love drafting, but I absolutely adore revising. I love tearing apart a story to make it better. I love poring over my sentences, trying to find the exact right rhythm or image or word. Generally, that love exists in day-to-day drudgery of the work, and it exists whether or not anybody else reads it. Or approves of it. Or cares.

External validation can be exhilarating. It feels like a jolt of self-esteem. (You like me! You really, really like me!) That makes it easy to crave and easy to chase, and it’s easy for that sense of rapture and jubilation to eclipse the quiet mundanity of the work. But in my experience, external validation is temporary on good days, withholding in general, and downright malicious at its worst. Furthermore, even when I’ve gotten it, external validation can be a threat to the work. (Got that fancy award? Congratulations! Now what if you can’t ever write a book as good? What if you’ve peaked, and you’ll never again live up to all your high-minded ambitions? What if the rest of your life is one agonizing slide into obsolescence? What about that?)

Yoking the euphoria of attention and perceived success to the love of the work is a burden to the work. It makes the work small, contingent not upon how much time/effort/skill/heart I put into it—which is what truly matters—but upon someone else’s extraneous measurements for success (or lack thereof). Moreover, it makes my love for the work conditional—if my love for the work burns brightly only in the presence of external validation, then without it, my love dims.

And I don’t want that for my work. Or myself. My best work is created when my love for it is expansive, confident, energetic. I feel proudest of myself not when someone else tells me I did a good job (although, Mom, if you’re reading this, I really like it when you tell me I did a good job) but when I can look at my work and say, Yes. I wrote the story I needed to write in the best way I knew how. I pushed myself to grow as an artist. I told a story I believe was worth telling, and I did it in a way consistent with my values.

It took me ten years and six novels to develop a robust approach to self-doubt, but looking back at that post from 2015, I can see its beginnings. First in despair, and then in defiance. I was sad and scared and upset and insecure, but I knew I did not want that. I knew it was paralyzing to me. I knew it would rob me of my work and my love for the work, if I didn’t do something about it.

So I did something about it.

A decade later, I feel steadier, older, less frantic, more patient, and I think that’s due in part to experience and some good fortune, but I also feel like I have this hard-won clarity now: The work is what’s important. My creativity is the root of the work. Therefore, I will do whatever it takes to protect my creativity.

I focus on the writing. I complain to my friends. I turn off social media. I take external validation with a grain of salt.

And when in doubt, I make more art.

In case you missed it

To celebrate Kindling’s first year in the world, I made a pretty little thing.

It’s kind of nice to celebrate some of the wonderful ways Kindling has reached readers. If you’d like to spread the love, feel free to share it on Instagram, Bluesky, Facebook, or Tumblr.

What I’m into these days

It’s a new year. How about some more poetry? Here’s one that resonated recently: “Chant of Immediate Threats” by Mai Der Vang, which I’ve been thinking about frequently as wildfires race across Southern California, and “My Project 2025” by Saeed Jones, which has a lot of wonderful lines, but right now I’m particular to the sound of “I’m Whitney Houston in the last verse / of ‘It’s Not Right, but It’s Okay.’” (For good measure, here’s “It’s Not Right, but It’s Okay”.)

I’ve been listening to Jon Batiste’s Beethoven Blues, which includes riffs and reimaginings of Beethoven as well as original works by Batiste, and it’s such a joy. I just like how much fun he’s having! See also: Batiste playing Für Elise for CNN’s Chris Wallace, Batiste playing Beethoven’s Fifth with pianist Alexis Ffrench, Batiste playing “Holiday” by Green Day, which he’s never heard before.

Every few years, my partner and I decide to make gingerbread houses for the holidays, and we always return to the same gingerbread recipe. Mary Berry’s recipe is hard enough to use for construction, but unlike some construction gingerbread recipes, it’s actually pretty tasty (if toothsome). If using for precise constructions, we recommend cutting out the individual walls, roofs, etc., baking, and trimming the pieces again as soon as they come out of the oven. For 2024’s gingerbread creation, check out the mostly-to-scale replica of the family cabin my partner and I made for my mom’s Christmas present.